Where are we—and what are we doing here?

Travel Section | Issue 1 | Sunday 03 May 2020

According to Skift Research, a media company that conducts research into the travel industry, a third of Americans want to travel again shortly after the current pandemic is contained. Where they want to travel is neither here nor there. The point is that right now roughly one hundred and nine million American people are thinking of or (depending on their time zone) dreaming of some kind of travel. That’s a lot of human beings on the hypothetical road, even though very few will be setting foot outside their neighborhood in the foreseeable future.

Why travel—why now?

Well, I can come up with a few reasons of my own just to get the conversation started.

Cabin Fever. I live on a tiny island in the smallest state in the union. (Yes, that one.) Yesterday I crossed two bridges over the waters of Narragansett Bay to take my car to the dealership on the mainland for an oil change. I haven’t been clocking many miles this spring but I keep the car in good shape, ready to go. Where to and when, I don’t know, but the minute I’m free to hit the road my car had better be ready to go with me. I live on Aquidneck Island, which has an area of just under forty square miles. From my home at the southern end of the island the farthest I can drive without hitting water or getting on a bridge is (almost) fifteen miles. It’s been a long stay-at-home spring and I have a pretty acute case of what we islanders call island fever right now. Heading to the mainland was a welcome expedition. Island fever, cabin fever, apartment fever. I’m not the only one, by far.

Road trip, anyone?

Boredom. This hasn’t been too much of an issue for me, thankfully. I’m a writer and a reader and I always think too much—it comes with the territory. I don’t need many tools to keep me engaged and occupied. I also work part time on a horse farm so I have a bona fide reason to get out in the elements most days. But I can imagine how many of those hundred and nine million people out there are bored to tears with each other and with the same old four walls, and are more than ready to break out and find a new view.

Necessary Journeys. Births and birthdays, deaths, sickness, and various rites of passage have been experienced or endured this spring in degrees of aching isolation. Some kinds of travel are just long overdue.

The Desire to Wander. A human instinct—an atavistic urge—that tests restraint at the best of times, and makes a pandemic stay-at-home spring an even bigger challenge. Perhaps thinking (and dreaming) of travel eases the discomfort of cabin fever, boredom, or isolation. Reading, planning, and plotting a route to a new view may be limited to a virtual experience for the time being, but it will always be a part of exploring and it won’t ever go out of style.

And On That Note. After a very necessary reading and media time-out, I recently re-subscribed to Sunday home delivery of The New York Times. I’d missed the familiar spread of color travel pages messing up the breakfast table, not to mention the Book Review (please tell me I’m not the only reader who gets heavily into it with a pen and highlighter in hand). The following week the newspaper announced that the print travel section would be suspended. I’m sympathetic to the challenges that the media are facing and I understand the reasoning, though the At Home section that has replaced the travel spread doesn’t elicit that same quickening when I open the front door in my pyjamas and pull a fat roll of newsprint from its blue plastic sleeve. I’m so glad I saved the excellent final edition, for old times’ sake.

The Best Laid (Travel) Plans

I spent the cold nights of February reading Colin Thubron’s delicate memoir To a Mountain in Tibet (read a review by Alida Becker, editor of The New York Times Book Review). Thubron’s account of his arduous solitary trek to Mount Kailash (at just under 22,000 feet) richly immerses the reader in landscape, culture, and history. It’s also a story of coming to terms with loss, as the voices of his long deceased mother and sister linger in the pages. I lingered over the book because there’s a pilgrimage of sorts on my own horizon. In the fall of this year I’m scheduled to trek to Tengboche Monastery in the Khumbu region of Nepal. I’ll travel with my husband and his siblings and our two sons to scatter my mother-in-law’s ashes. My mother-in-law was an intrepid explorer and Tengboche was where she wished to return, one last time. Our plans are on hold and will almost certainly be postponed by a year. Nepal is still in lockdown and according to The Kathmandu Post its government must repatriate approximately half a million citizens who have been working abroad, many of whom have lost their jobs due to the pandemic. My mother-in-law’s ashes will wait.

Meanwhile, I’ll be one of the hundred and nine million Americans thinking (and dreaming) of travel. It may be a flight or a road trip or, for the time being, a drive across the bay—who knows? A thousand and one reasons to travel, and almost as many ways to go.

Meanwhile, My Bookshelf.

My first taste of long form travel literature was Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands, a mesmerizing account of his wanderings, between 1945 and 1950, through what was then known as the Empty Quarter of Arabia. Published in 1959, Thesiger’s book is an intimate and respectful story of the people and tribes among whom he lived. Arabian Sands has been described as ‘a classic account ... invaluable to understanding the modern Middle East.’

I’ve just reached the last quarter of Jill Ker Conway’s memoir The Road from Coorain with that sinking feeling that it will end soon and I won’t be able to fill the void—the litmus test of a compelling narrative. The book narrates Ker Conway’s childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood in Australia, from hard early years on an isolated sheep-farm to the seeds of an impressive academic career. In 1960, at the age of twenty-six, Ker Conway left the professional and personal confines of her homeland and emigrated to the United States. She studied history at Harvard and went on to become the first woman president of Smith College. In a later essay titled Points of Departure she wrote:

Philosophically, you only have to perform one free act to be a free person. Granting all the ways in which we’re shaped by society, nevertheless one free choice changes the outcome.

I remember taking the first big step outside the confines and expectations of my own homeland. This is from my essay collection Beyond Ithaka, Private Journeys in a Public World:

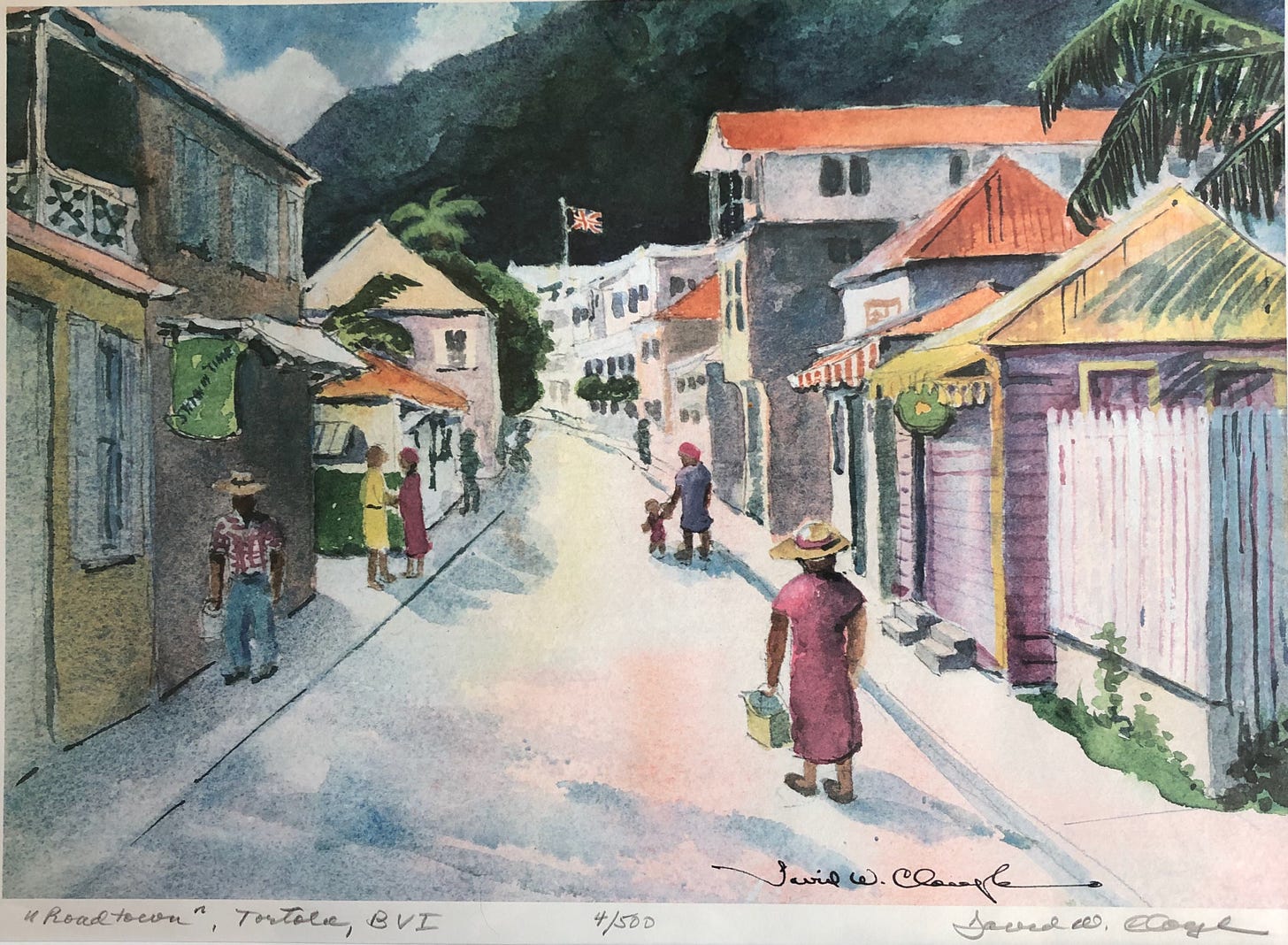

It was 1981 and I was twenty-three years old, barely a year out of university. I boarded my first flight, fastened my seatbelt, and closed my eyes to everything that was familiar. When I opened my eyes, it was to the blinding sunlight of the West Indies. I had landed in a world of breathless heat, unworldly blossoms, the shrill of tin calypso, smiling toothless taxi drivers, and carnival food that was cooked in no mother’s kitchen. Quite by accident I lived in this idyll for almost a decade.

A journey had begun. I had performed one free act and set forth on a life of exploring. I don’t know the outcome yet. But the road so far has been very colorful.

I’ve enjoyed writing this first newsletter for Travel Section. I wanted to explore some ideas and to acknowledge some of the experiences and emotions that people are grappling with. It’s also reminded me of the marvelous journey I’m on. Thanks for reading. I’ll welcome your comments.

If you’ve enjoyed this first edition of Travel Section please think about subscribing to the newsletter. It’s free, it’s fresh, and it lands in your inbox on Sunday morning. You can unsubscribe at any time.